In the 1880s, you could be fined for being ugly in public.

And they were no joke either; the laws were not just about morning puffiness or acne breakouts.

They came with stringent definitions of ugliness that cut across social classes and economic statuses.

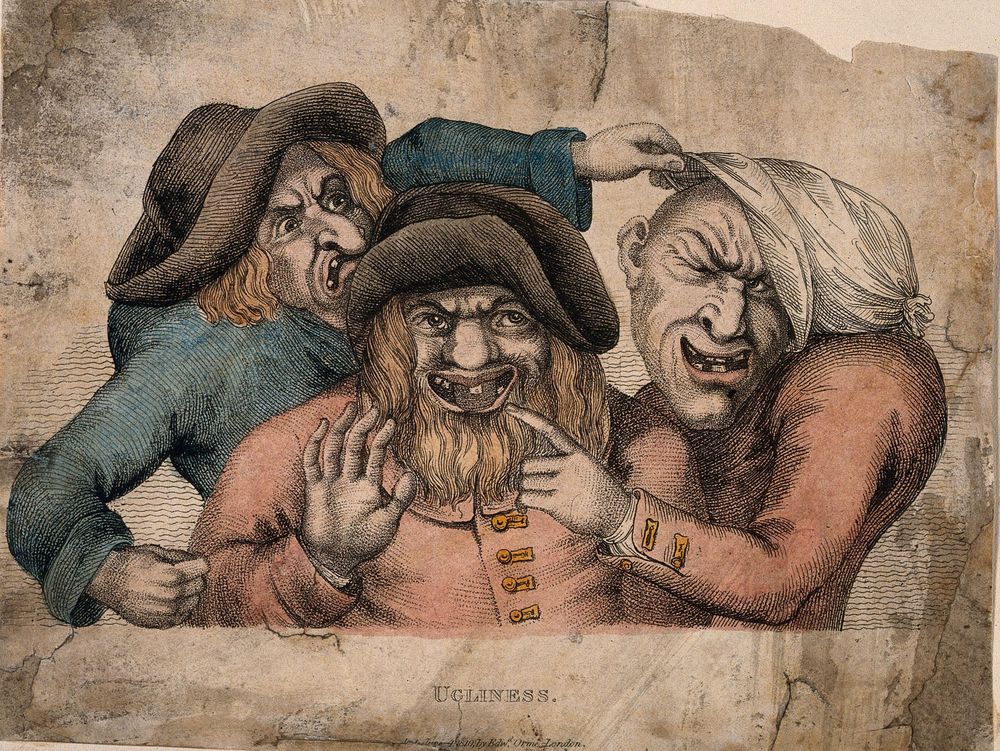

Three grotesque old men.

Such strained versions of the ugly laws were welcomed by the public.

An article in theChicago Tribunecalled the removal of unsightly beggars from the streets as a public benefit.

But he also mandated an exemption for maimed soldiers out of respect for war veterans.

This included bans of jobs as well social discrimination for various groups of physically deformed persons.

This sweeping of the economically backward disabled persons became the strongest undertone of these ordinances.

The chasm between the rich and poor, accepted and unaccepted, thus began to deepen.

By that definition, even tramps were soon included in the same conversation with disabled non-workers.

The belief was that if you could hold a job, you were worthy.

If not, you were ugly.

Industrial workers too were exempted from the law as long as they could find work and support themselves.

For how long could a blind woman continue her work as a seamstress?

The lines between anti-beggar legislations and the ugly laws were thus allowed to blur.

The underlying notion remained that if you could support yourself, you were worthy.

If not, you were ugly.

The laws thus applied to the public more on economic grounds than on appearance.

Only by the end of the first World War were sensitivities triggered.

As soldiers thronged back deaf and blind or missing a limb, mentalities shifted towards acceptance of the disabled.

By 1974 the law had already been repealed.