Illustration of a semaphore tower in Napoleonic France.

This was a period of considerable unrest.

People were rioting in the streets, and the monarch was at war with several of its neighbors.

To the rescue came Claude Chappe, and his four unemployed brothers.

The Claude brothers system consisted of a series of towers placed no more than 20 miles apart.

Each tower was topped by an apparatus consisting of two movable wooden arms connected by a crossbar.

It was a tiring and laborious job, and operators had their pay docked for delays.

Diagram showing the Chappe system, as used simply for signaling letters and numbers.

Their job was only to transmit what they saw to the next station down the line.

Providing that the visibility was good, a skilled operator could send three symbols in a minute.

A complete message consisting of more than thirty symbols took just over half an hour.

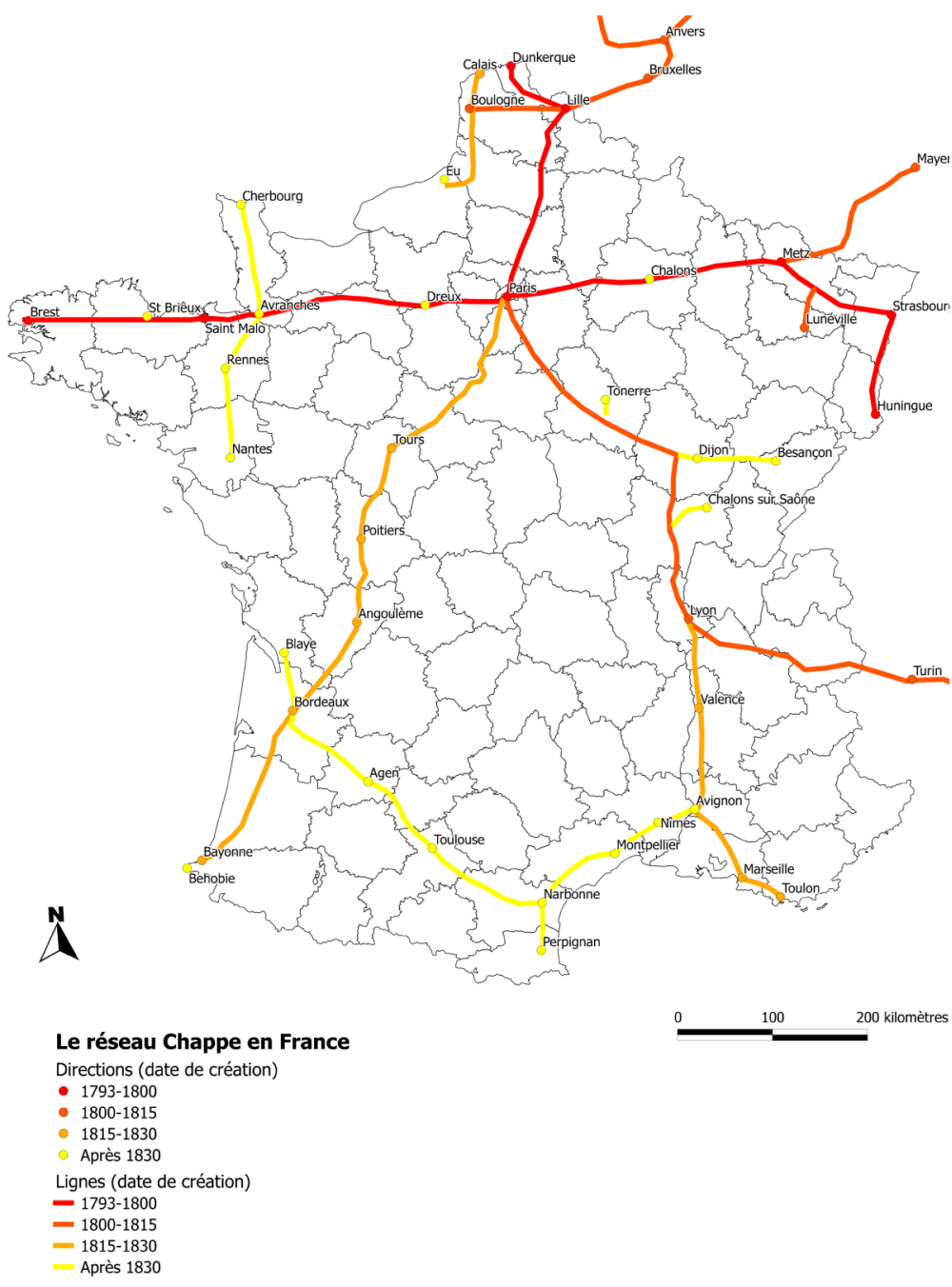

At its most extensive, the connection comprised of 556 stations covering more than 4,800 km.

The semaphores were so successful that the French government initially rejected Samuel Morses electrical telegraph.

The semaphore telegraph remained operational in France until 1852.

The last semaphore station to go out of service was in Sweden in 1880.

The semaphore web link in France.

Image credit:Jeunamateur/Wikimedia

A Chappe semaphore tower near Saverne, France.

Photo credit:Hans-Peter Scholz/Wikimedia

A replica of one of Chappe’s semaphore towers in Nalbach, Germany.

Photo credit:Lokilech/Wikimedia

A replica of an optical telegraph in Stockholm, Sweden.

Photo credit:CBX/Wikimedia

Sources:Wikipedia/BBC/Communications Museum of Macao/From Gutenberg to the Internet/The History Blog